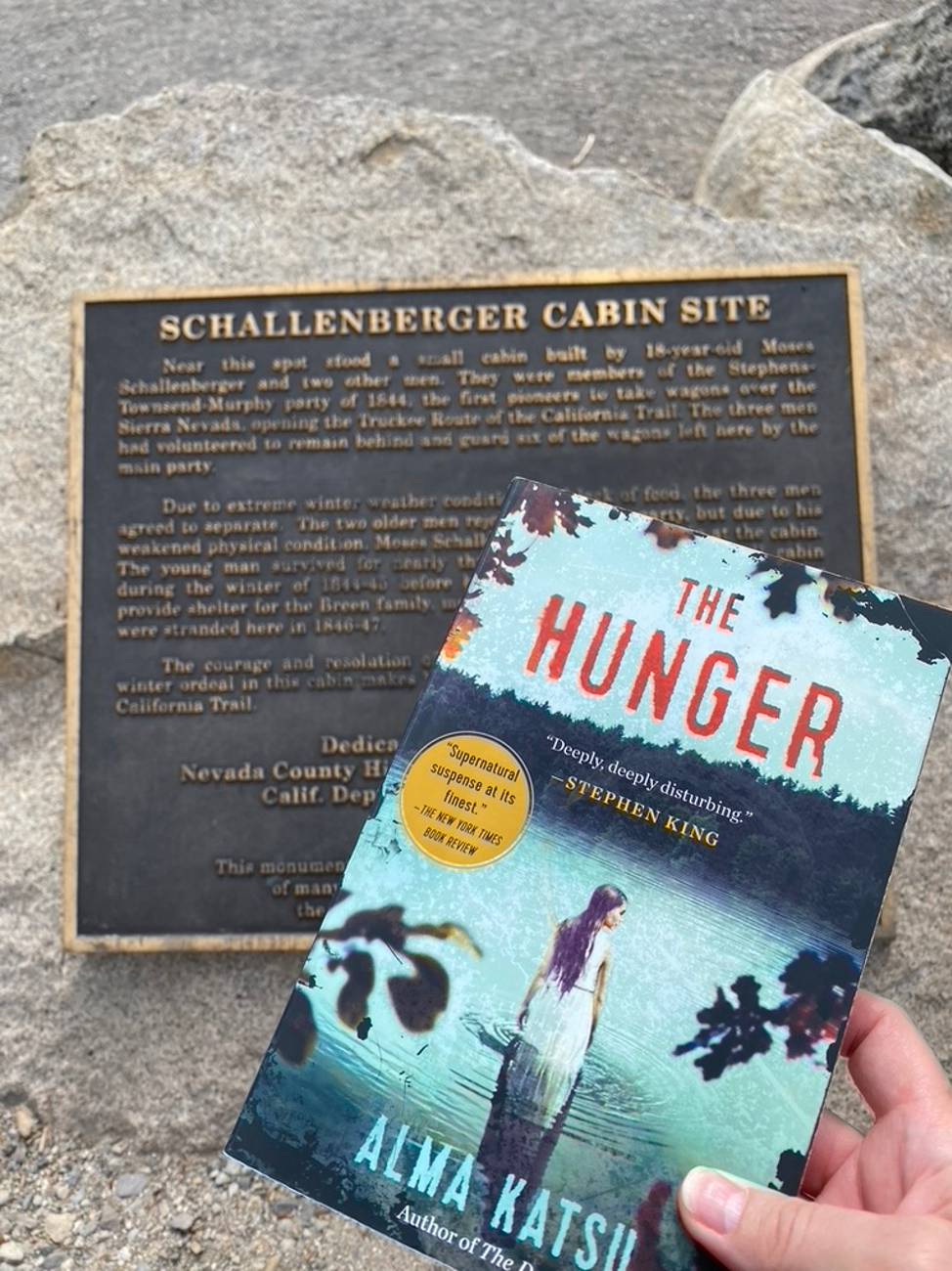

Short answer: Because textbooks are limited in breadth and depth to a handful of famous people and key events. I want to know the other narrative, the one that deals with real everyday people. Historical fiction provides the jumping off place for discovering the social interactions, the personal interactions, that complete the picture of what happened. While there is a fictional element, usually an underlying story to add interest, good historical fiction is well researched. Historic fiction authors portray events and people more realistically than what we’re taught in school. Let me explain using Alma Katsu’s historic fiction horror novel, The Hunger, a re-telling of the Donner Party expedition, and a road trip from this June.

On the Denver to Reno leg of a cross-country trip, I listened to The Hunger. Somewhere west of Salt Lake City, I realized I was following the same short cut as the Donner Party!! I saw Fort Bridger, experienced the desolation of the Nevada desert, and encountered the dizzying heights of the Sierra-Nevada mountains. I imagined I was a pioneer, making the journey in a wagon. I was hearing and seeing the trek this unfortunate group made in 1846-47.

I would have made a horrible pioneer, by the way. In a car with air conditioning and snacks, the drive from Salt Lake City to Reno sucked—a long, monotonous drive with no open rest stops for 596 miles, a modern inconvenience that forced me to consider how pioneer women relieved themselves. In case you’re unfamiliar with this, allow me to explain: Salt Lake City to the Nevada border is a salt flat. The Nevada-Utah border to Reno is a desert. Hundreds of miles of nothing but salt and sand. It’s so flat, you can see the future. My point being: I was traveling comfortably, yet I felt isolated and irrelevant as I stared into the flat horizon of nothing. Venturing beyond Reno, I entered the mountains, the same ones traversed by thousands of pioneers headed to California in the 1800s.

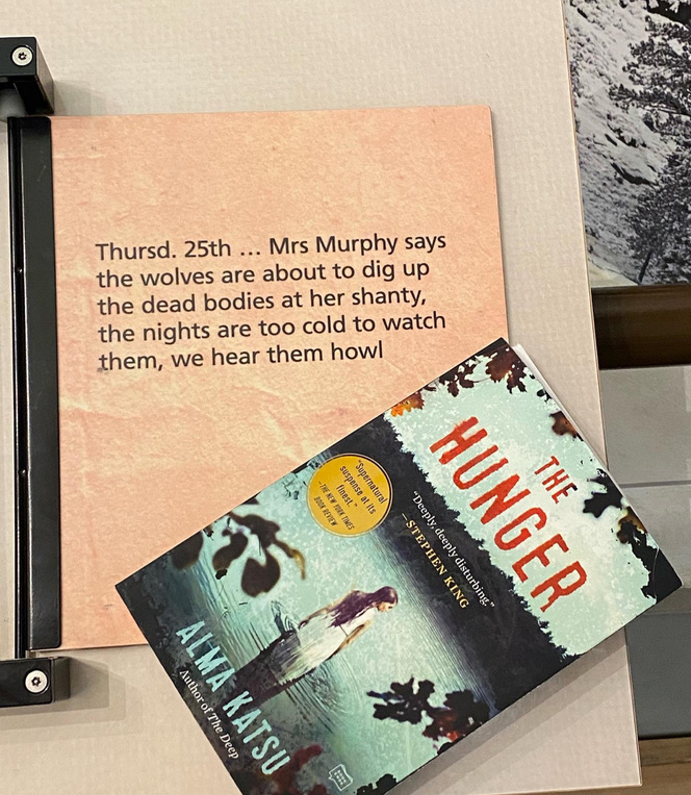

Using Trip Advisor as my guide, I discovered Donner Memorial State Park was on my way. Thanks to well-written, info-panels in the museum and a tour by the lovely, knowledgeable Mary, I learned that most of my knowledge about this Great American Mishap was wrong. And what Katsu had written was a much more accurate depiction of the people and events than I had been taught. What types of things, you may ask? Well…

- Several families comprised the Donner Party. The Donners just happened to have more members not survive the trip than others. Yes, the least successful family is the most famous. As the museum info-panel declared, “Other groups of emigrants crossed this route successfully before the Donner Party made it famous through failure.” Fair point.

- This was not a new route. Matter of fact, it had been in use for at least two years, with thousands of successful crossings. This one? Not so much. Why?

- This group decided to take shortcuts. Their inspiration for this was one sentence in a book by Lansford Hastings. One sentence! They were to meet at Fort Bridger for a personal escort. He didn’t show. They went anyway. Because why not? What could go wrong?

- Let’s talk about trails and passes:

- I was taught trails along rivers are worn and clearly marked. Nope. Pioneers did follow the rivers, but actual sections had to be bushwhacked for them to pass. Apparently, this takes time.

- Trails in the desert…I couldn’t picture this as it’s all dust all day. While the trails were visible, the problem was water, specifically, water for animals. Nowhere in school were the animals, or their needs, discussed. Nor the invaluable need for these animals to human survival.

- I was led to believe mountain passes are like a trail, but narrow—difficult to navigate in snow, of which there were copious amounts. Nope and Nope. To climb high mountain passes, the wagons were disassembled and hauled up by ropes (as were the oxen) along sheer rock. Extremely dangerous and time-consuming. Then were re-assembled before the journey could continue.

- The people who made the journey West were not, as I had been told, out of options back east. They were not persons who had nothing to lose by heading into the western territories. These were people of means! Entrepreneurs. The amount of money it took to undertake this venture was staggering. They hired teams of drivers!

- The women survived, for the most part. Why? Because we’re smaller and don’t require as high a caloric intake as men. Bonus: higher fat stores. Thick paid off.

- No one ever mentioned the very real danger for women: rape and sexual assault. Didn’t matter if you were with your family, your husband. The potential for sexual assault was constant.

- Also never mentioned: infighting fractured the group. It makes sense: all the men with money wanted to be captain, even though they’d never made the journey nor had any experience with leading an expedition. It feels cliché—it is cliché, but this pissing contest between the men led to wasted time, depleted supplies, and needless death. As I state in my novel, The Isle of Devils, “Men die of hubris; women die for family.” Truth.

Thanks to Katsu’s novel, I was able to better interpret the history. I was familiar with the names and dates before stepping into the museum, and her portrayal of the principle parties was spot-on. Incompetent Men + $$ = Power—a constant trope throughout history. But Katsu’s skillful portrayals allowed others their say. As Tears for Fears told us in the ‘80s, the 1980s, “Everybody wants to rule the world.” Historical fiction humanizes the why in ways that textbooks cannot.